Run Training: Heart Rate, RPE, MAF, Power and Pace

Karen Parnell

January 12, 2022

Karen Parnell

January 12, 2022

Run Training: Heart Rate, RPE, MAF, Power and Pace

What is best? Heart Rate, MAF, Power or Pace?

There are many ways to perform run training and it’s important to find what works for you. Some athletes prefer running to feel using RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion), using heart rate or even power.

In this blog I will discuss the different methodologies and the pros and cons of each one so you can select one to try that will meet the way you like to train.

Rate of Perceive Exertion (RPE)

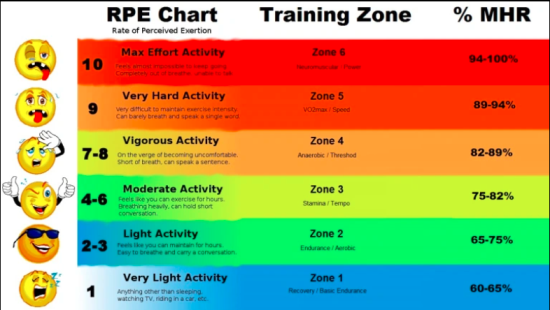

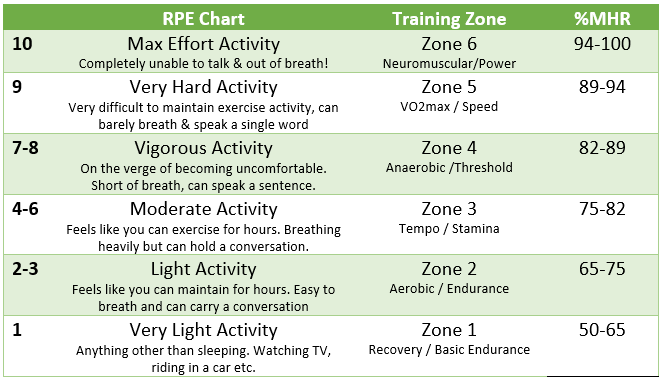

RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) is a scale used to identify the intensity of your exercise based on how hard you feel (or perceive) your effort to be. Some people call this “running by feel”. The RPE scale typically runs from 0 to 10, with zero being literally nothing and 10 being the hardest you could possibly exert yourself.

For example, a 7/10 RPE means you should be at about 7 out of 10 in terms of perceived exertion or about 70% effort.

One thing to note: RPE is a subjective measure of how hard something feels both physically and mentally for you in that specific workout on that specific day. You might perceive the same effort as harder or easier on a different day for any number of reasons, your fatigue level, illness, weather, even mental fatigue make a workout feel harder. That’s why RPE is commonly used as just one metric among a number of tools to help fine tune your training.

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

Why Use RPE?

You’ll see RPE referenced in some of my training plans on TrainingPeaks, Final Surge and Training Tilt. While you may have target paces or heart rate zones to hit, RPE provides a more universal scale to measure exercise exertion.

The other benefit of RPE is that it gives you a check on more objective measures like heart rate or power. You might have established your training zones with an FTP test or extrapolated them from a long race effort; that then gives you target heart rate zones to hit for various efforts and corresponding power numbers on the bike or paces on the run and in the pool. But there are workouts where you’re hitting the pace, power, or heart rate numbers—and yet your perceived exertion feels off. Think of those days the tempo workout feels like an all-out sprint! That’s where RPE can come in handy as an additional piece of information to check your intensity

The longer you pay attention to your RPE too, the more you’ll fine-tune it. As you hit your paces and numbers in workouts, you’ll also learn what Olympic-distance pace or 70.3 effort feels like. And you’ll learn to listen to your body.

How Do You Know What Your RPE Is?

Originally, the RPE scale was established as the Borg Scale of Perceived Exertion and the scale went from 6 to 20. The idea was that if you added a zero to your perceived exertion, you’d get your approximate heart rate. For example, a 12 on that scale would correspond with about 120 heart rate—which is considered “fairly light” activity on the Borg scale, such as brisk walking.

In the 1960s, that scale was changed to an easier to understand 0 to 10, but the rough guidelines are still applicable.

Strava, for instance, uses RPE as a metric you can add to your workouts. Here’s how they define the 0 to 10 scale:

– Easy (1-3): Could talk normally, breathing naturally, felt very comfortable

– Moderate (4-6): Could talk in short spurts, breathing more laboured, within your comfort zone but working

– Hard (7-9): Could barely talk, breathing heavily, outside your comfort one

– Max effort (10): At your physical limit or past it, gasping for breath, couldn’t talk/could barely remember your name

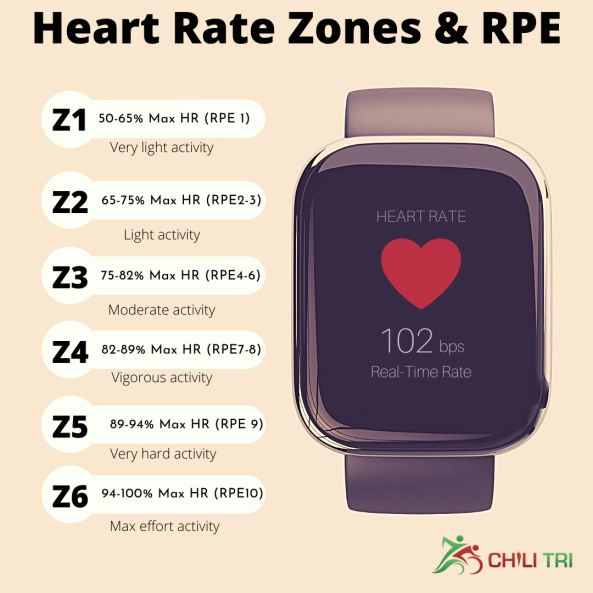

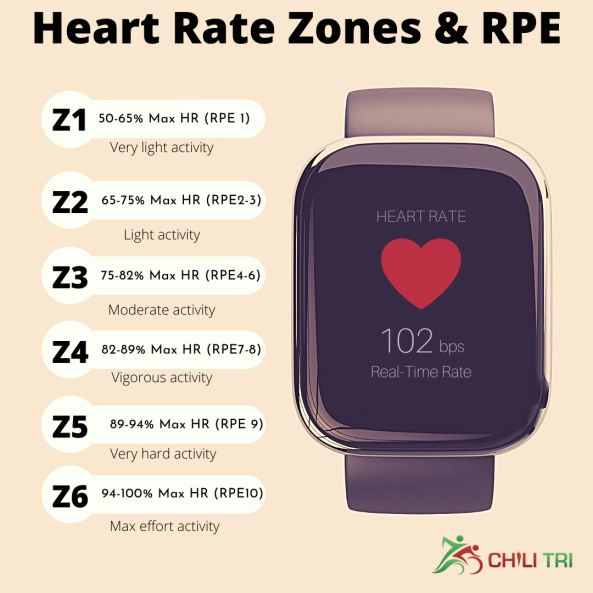

I like the table below from John Heltzen showing RPE and it's relationships to Heart Rate Zones and Maximum Heart Rate.

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

Understanding Heart Rate Zones

Probably the most common way to train is with heart rate and heart rate zones. Most sport watches such as those from Garmin, Polar, Apple, Fitbit etc have a built in optical heart rate monitor. If your watch does not use have a built in HR monitor you can use a HR chest strap if your watch supports Bluetooth or ANT+.

In training plans you will see heart rate training zones such as:

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

Each zone will be selected based on your desired training session outcome. For example Zone 1 to 2 training will be used for long base or endurance runs. Zone 1 and 2 training is important because the benefits of these workouts. You build endurance, durability and strength. If you have a high intensity session they you will be aiming for zones 5 and 6. These efforts increase your anaerobic power and develop your VO2 max, the maximal amount of oxygen that can be used during exercise for the development of sustained power.

Get some FREE resources including training plans here.

Training with heart rate these days is very easy with training platforms such as Final Surge and watch manufacturers like Polar calculating them for our based on your age. Here’s a chart showing the heart rate zones, RPE, maximum heart rate and the talk test:

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

MAF (Maximum Aerobic Function)

The MAF Method was developed by nutrition, exercise and sports medicine expert Phil Maffetone in the 1980s after 40 years of research. MAF stands for Maximum Aerobic Function, and focuses on the aerobic system, the fat burning engine of your body. MAF is not just about running or training but achieving a lifestyle that helps you control chronic inflammation; manage stress, burn fat and more. But for the sake of this blog, we will look at its impact on running.

The MAF method for running uses your heart rate as a basis for making sure you are using fat as a fuel source and to adapt your endurance training.

It must be noted that Maximum Aerobic Function (MAF) is more than just heart rate and you can read more about it and Phil Maffetone here.

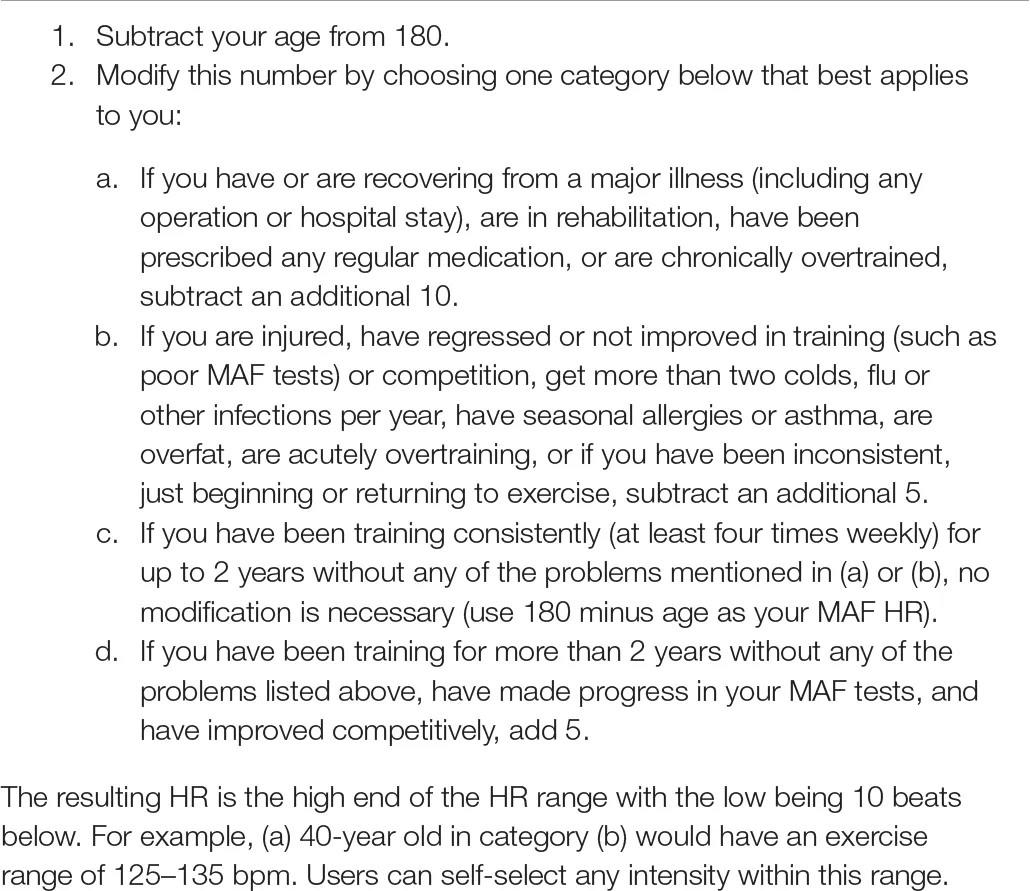

First you need to calculate your MAF heart rate (HR) which is simply subtracting your age from the MAF method's ideal training heart rate of 180. You can use the ChiliTri MAF calculator for this. This is the basic calculation, but you can tailor it to your current situation. For example, if you are recovering from an injury subtract an extra 10. If you usually have allergies or catch a cold quite often, subtract five more. If you have trained consistently for at least two years without any major injury, add five. In this way, you arrive at your ideal current training heart rate. The idea is to find a pace that is comfortable enough for you to let you run for hours, without letting the heart rate spike.

It may take weeks or months for your body to adjust to this long run style and you may find you need to walk to keep your MAF HR and this is normal. Over time your body will adjust and you will find you will be able to go on long runs and stay in your MAF zone for the whole run and know you are tapping in to your bodies fat store to fuel your run. You will feel like you can run for hours! But you need to be patient and trust the process!

You will also find that you will be able to recover quicker after each long run and also it will help you avoid injuries associated with running.

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

Once you have adjusted your body you can start to add in high intensity sessions. Studies have proven that this method of training will help you get faster even if it is counter intuitive. According to MAF, the way to a better and faster run is to first slow down.

In this training zone we stimulate Type 1 muscle fibers, therefore we stimulate mitochondrial growth and function which will improve the ability to utilize fat. This is key in athletic performance as by improving fat utilization we preserve glycogen utilization throughout the entire competition. Athletes can then use that glycogen at the end of the race when many competitions require a very high exercise intensity and therefore a lot of glucose utilization.

Besides fat utilization, type I muscle fibers are also responsible for lactate clearance. Lactate is the byproduct of glucose utilization which is utilized in large amounts by fast twitch muscle fibers. Therefore, lactate is mainly produced in fast twitch muscle fibers which then, through a specific transporter called MCT-4, export lactate away from these fibers. However, lactate needs to be cleared or else it will accumulate. This is when Type I muscle fibers play the key role of lactate clearance. Type I muscle fibers contain a transporter called MCT-1 which are in charge of taking up lactate and transporting it to the mitochondria where it is reused as energy. MAF training increases mitochondrial density as well as MCT-1 transporters. By training in the MAF zone we will not only improve fat utilization and preserve glycogen but we will also increase lactate clearance capacity which is key for athletic performance.

An endurance athlete should never stop training in the MAF zone. The ideal training plan should include 3-4 days a week of zone 2 training in the first 2-3 months of pre-season training, followed by 2-3 days a week as the season gets closer and 2 days of maintenance once the season is in full blown.

Think of it as a way to build your body's capacity to run faster. When you're running slowly, your body is increasing its mitochondria and capillary production and making it easier for you to run faster the next time you face a hard training run or race. It's laying the groundwork you need to improve as a runner.

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

Training By Pace For Running

Another way of training is run by pace to improve your run performance and to make sure that you know exactly what pace you are aiming for on each run.

Examples of run paces are E-pace, M-pace, T-pace and I-pace.

EASY

E-pace is 'easy pace' - the key pace for most triathletes to train at. It's a comfortable, conversational pace.

Key physiological benefits: The heart muscle is strengthened; muscles receive increased blood supplies and increase their ability to process oxygen delivered through the cardiovascular system.

MARATHON

M-pace is 'marathon' pace, used to help prepare runners for the demands of a long hard marathon race. It's also a very useful pace for triathletes, especially training for a 70.3 triathlon. Few triathletes are able to run a marathon at their M-pace - unless they committed to preparing for the marathon like a 'runner' would do i.e. very high mileage, running every day, often twice a day. For most triathletes, this is likely to be closer to their half marathon pace.

THRESHOLD

T-pace is the pace you can sustain at functional Threshold. This type of training taxes your ability to tolerate and clear lactic acid. In a very motivated race, you might be able to hold this pace for an hour. In training, it is usually used for longer reps of 5-15 minutes, or 'comfortably fast' tempo runs of 3-4 miles.

INTERVAL

I-pace is your pace at VO2max, the pace that forces your muscles to absorb the maximum amount of oxygen they can per minute. You might be able to hold this pace for 15 minutes when highly trained in a race. In training, we usually us it for reps of 3-5 minutes. This is the fastest running that we schedule for our runners at oxygenaddict.com due to the risk of injury and severe soreness greatly increasing above this pace.

RUNNER EXAMPLE: CALCULATING YOUR T-PACE and I-PACE

To take the example of a runner who has a PB (personal best) of 20 minutes for 5k:

T-pace - 1.43 per 400m, or 6.53 per mile.

I-pace - 1.34 per 400m, or 6.19 per mile

The aim of your training is to get the optimum result from the least possible training stress. Don't be tempted to push yourself 'a little faster' than either of these paces. Training a little faster than prescribed pace is possible (in the short term at least) - but you won't be doing yourself any extra good.

In the example above, our 20-minute 5km runner could choose to 'push them self' during a T-pace session and run their 1-mile repeats in 6.40 per mile instead of their T-pace of 6.53. They would be physically capable of doing it, after all, their I-pace is 6.19 per mile. However, all they will accomplish is to increase the amount of time it takes to recover from the session. They will not increase the 'training effect' of their session by having 'pushed them self' a bit harder, in fact, going too hard early in a run session simply means that later in the session the athlete is too tired to even sustain T-pace - and the overall effect is a reduced training effect!

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

Running with Power

Running power, measured in Watts, is a way to measure the output of the work you’re doing when you run. The higher the Watts, the more power you’re generating with every step. The more power you can generate at a lower heart rate or faster pace, the more efficient you are. And efficiency is the secret weapon of fast runners.

Power can be used with a certain degree of accuracy to the reflect the metabolic cost of your efforts and offers a new way to measure the load on your muscles.

Cyclists have been using power for a long time as a great way to produce consistent performance in both training and racing. But power has taken a while to make its way to running because unlike cycling where you’re working in a fixed position, there are far more biomechanical and situational variables that make it much harder to generate accurate and useful data.

However, with smaller and increasingly powerful sensor technology (accelerometers) products are coming onto the market that bring power to runners too.

As with any biomechanical measurement there’s still a healthy scientific debate about how best to measure running power, what’s actually being measured and how to apply it. Unlike power meters on bikes running power is usually a calculation rather than an absolute figure direct from a power sensor.

There are various ways to getting running power data from foot pods like Stryd, some watches provide a calculated figure like Garmin and integrated on newer watches such as the Epix 2 with the Running Dynamix Foot Pod (read more here) and you can collect this from devices like the INCUS Nova. There are also chest heart rate monitors like the Wahoo TICKR-X what give you calculated power.

The power P is calculated from your body weight m in kilograms, the acceleration a (m/s2) and the speed v (in m/s) using the formula:

P = F*v

F = m*a

You will see the power figure quoted as Critical Power (CP), rFTPw (running functional threshold power) and Watts.

Get your FREE guide to Running Technique E-Book

Benefits of Running with Power

Power sensors react in real time with every step so are great for sprints, hills and track sessions.

Power tracks the actual output rather than your heart’s response to the work needed to produce the output, or the result of that output in speed or pace, it’s possible to get a consistent reading that reflects your work rate whether you’re running on the flat or uphill.

If you run a flat stretch at 230 Watts and your pace equivalent is 8-minute miles, when that flat turns into a steep hill, in order to maintain a steady 230 Watts, the chances are you’re going to have to slow down. But the work you’re doing to maintain the even wattage will be the same.

There are some caveats to this. Wind and heat are two external factors that most power metres can’t read (Stryd has a version that measures wind), another is softer ground underfoot. Running downhill presents some problems too but overall the stats you get are a reliable guide to what’s actually going on.

Running with Power with a Stryd Footpod and Garmin GPS Watch

Pacing using Power data

One of the most promising practical applications for power is helping to pace races evenly.

The best power-tracking devices offer calculators that let you quickly assess what power you’ll be able to maintain for any distance, certainly up to a marathon.

The Stryd partner app, for example, takes a recent 5k, 10k, half or marathon time, lets you select your target race distance (from the same distances listed here) and then provides you with a target in Watts. This power target, a single number, represents the output you can sustain without breaking your threshold and heading for the wall.

What that means in practice, is that by sticking to this one number, you can control your race from start to finish without the risk of blowing up. You might even find you have a little more to give in the final miles or kilometres, but you’ll at least be in a position to make a decision.

There is an important surprise here though. You don’t get to decide your target time. Instead, you have to trust that the power target you calculated will give you the race outcome your training deserves. You’re no longer aiming for a time you’ve decided you think is possible and that’s quite a hard concept to grasp.

It shifts the emphasis from what you think you might be able to do to what your current objective fitness will allow you to do.

If you’ve trained well and your race power target calculations are done correctly, you’ll be in with as much of a chance of a PB with a run that’s not ruined by a poor pacing strategy.

Get some FREE resources including training plans here.

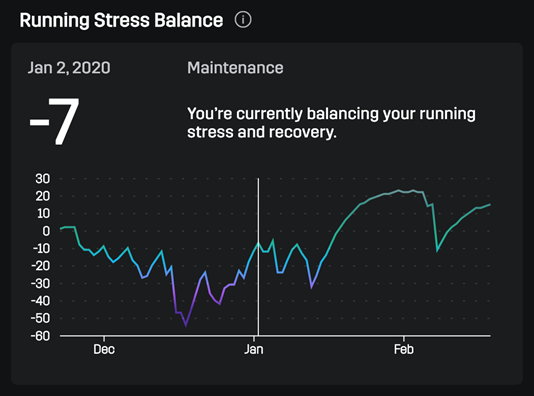

Spotting improvements in your Performance

Used in conjunction with heart rate, power is a great tool for identifying improvements in performance. For example, if you repeat the same session two weeks apart and you find you’re running at same power but with a lower heart rate, that’s a sure sign of better efficiency, aka an improvement in your running form. The same goes for producing equivalent pace to power.

Managing your Training Load

When you run you are placing stress on two systems, the cardiovascular system and the muscular system. While heart rate can track cardio load, before power metres we didn’t really have a way to measure the strain on the muscles.

Power Training Zones

Just as you can with heart rate, it’s possible to generate power-based target zones for the different running states including recovery, steady, threshold and tempo, VO2 Max and speed work interval sessions and repetitions.

Because there’s no time lag with power, you can hit these zones more quickly and more accurately than you would using heart rate. For example, you can ensure you’re training in the 80-85 percent threshold zone from the very first 100 metres.

Endurance Training in the Heat

In hot weather your stats for Heart Rate will change. If you want to know more about how heat affects your running and cycling then you can read my Blog on triathlon training in the heat, it's benefits and how to gauge your training zones.

Conclusion: Training Zones

As you can see there are many ways to gauge intensity when you are running and it’s important to see which one works for you.

Having a system that suits you means that each running session is valuable and not wasted miles. You can make sure your high intensity sessions give you the right physiological result and that your long runs are at the right level to ensure you building your base correctly.

Train at the pace or intensity prescribed for the session. It will give you the optimum result from the least possible training stress and will ensure you can recover quickly, so you can train again!

Get some FREE resources including training plans here.

Would you like a free training plan? Claim your free plan or e-book.

Karen Parnell is a Level 3 British Triathlon and IRONMAN Certified Coach, 8020 Endurance Certified Coach, WOWSA Level 3 open water swimming coach and NASM Personal Trainer and Sports Technology Writer.

Karen has a postgraduate MSc in Sports Performance Coaching from the University of Stirling.

Need a training plan? I have plans on TrainingPeaks and FinalSurge:

I also coach a very small number of athletes one to one for all triathlon and multi-sport distances, open water swimming events and running races, email me for details and availability. Karen.parnell@chilitri.com

Get your FREE Guide to Running Speed and Technique

Get your FREE Swim Workouts for Triathletes E-book

Get your FREE Open Water Swimming Sessions E-Book

FAQ: Heart Rate, MAF, RPE and Power

What is heart rate training for running?

Heart rate training for running involves using heart rate zones to guide the intensity of your workouts. This approach helps you train at the right level for your fitness and goals, and can improve your endurance, speed, and overall fitness.

What is RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) training for running?

RPE training for running involves rating your perceived exertion during workouts on a scale from 1 to 10. This approach helps you listen to your body and adjust your workout intensity accordingly, which can be particularly useful when heart rate monitors or power meters are not available.

What is MAF (Maximum Aerobic Function) training for running?

MAF training for running is a type of heart rate training that focuses on improving your aerobic fitness by training at a heart rate that corresponds to your maximum aerobic function. This approach can help improve endurance, speed, and fat burning, and can reduce the risk of overtraining and injury.

What is power training for running?

Power training for running involves using a power meter to measure your power output during workouts. This approach can help you optimize your training intensity and improve your running efficiency, particularly if you are training for long-distance races or triathlons.

What is pace training for running?

Pace training for running involves focusing on your running speed or pace during workouts. This approach can help you improve your running form, build endurance, and increase your speed and overall fitness.

How do I choose the right training approach for me?

The right training approach for you depends on your fitness level, goals, and personal preferences. You may want to experiment with different training approaches or consult with a running coach or trainer to help you develop a customized training plan that works best for you. Power tends to give instantaneous feedback whereas heart rate has a lag between effort and heart rate changing.

How often should I change up my training approach?

The frequency at which you change up your training approach depends on your goals and preferences. Some runners may prefer to stick with one training approach for an entire season or training cycle, while others may switch things up every few weeks or months to keep their workouts fresh and challenging.

Can I combine different training approaches in a single workout?

Yes, you can combine different training approaches in a single workout, such as using heart rate zones to guide your warm-up and cool-down and focusing on power or pace during the main workout. Just be sure to balance the volume and intensity of your workouts to avoid overtraining and injury.

What is running with power?

Running with power involves using a power meter, such as Stryd, to measure the power output of your running stride. This approach helps you track your running intensity more accurately than relying on heart rate or pace alone.

What is Stryd?

Stryd is a power meter specifically designed for running. It attaches to your shoe and measures your power output, as well as providing other metrics like cadence, ground contact time, and vertical oscillation.

What is rFTPw?

rFTPw (running Functional Threshold Power with wind) is a metric developed by Stryd that estimates your running threshold power, or the highest power output you can sustain for an extended period. This metric considers factors like wind resistance, temperature, and elevation to provide a more accurate estimate of your threshold power than traditional methods.

How does running with power differ from heart rate or pace training?

Running with power provides a more direct measure of your running intensity than heart rate or pace alone, which can be affected by factors like fatigue, temperature, and terrain. By using power as a guide, you can more precisely control your running intensity and optimize your training to achieve your goals.

How do I get started with running with power and Stryd?

To get started with running with power and Stryd, you will need to purchase a Stryd power meter and sync it with a compatible device or app. You may also want to consult with a coach or trainer to help you develop a training plan that incorporates power-based workouts. You can get 15% of a Stryd device using code COACH-PARNELL.

How do I use rFTPw to set my training zones?

To use rFTPw to set your training zones, you will first need to perform a baseline test to determine your current threshold power. You can then use this value to calculate your power-based training zones, which are typically based on a percentage of your threshold power.

How do I incorporate power-based workouts into my training plan?

To incorporate power-based workouts into your training plan, you can use power as a guide to adjust the intensity and duration of your workouts. For example, you could do interval workouts based on your power output or use power to guide your pacing during long runs or races. You can find my power-based plans here.

Can I combine power-based training with heart rate or pace training?

Yes, you can combine power-based training with heart rate or pace training, depending on your goals and preferences. Just be sure to monitor your overall training load and adjust your workouts accordingly to avoid overtraining and injury.

How often should I retest my rFTPw and adjust my training zones?

The frequency at which you retest your rFTPw and adjust your training zones depends on your goals and preferences. Some runners may retest every few months, while others may wait until they see significant improvements in their performance before adjusting their zones.

References

MAF training

https://philmaffetone.com/180-formula/

Running with Power

Running using Pacing

https://www.runnersworld.com/training/a20807849/proper-pacing-will-make-you-a-better-runner/