Triathlon training in the heat, it’s benefits and how to gauge your training zones

Karen Parnell

June 14, 2022

Karen Parnell

June 14, 2022

Triathlon training in the heat, it’s benefits and how to gauge your training zones

Get your FREE Guide to Running Speed and Technique

The temperatures rise in the summer months, and this will change the way your body responds to training, how it adapts and how you plan for each session.

There are physiological benefits, but you may need to think about your training and race goals in order to get the most from each session.

In this article we will look at the benefits of training in the heat, a heat training hack, how to adjust your sessions and zones to take account of the conditions and most importantly how to stay safe.

Many triathletes like you may have heard that training in the heat can help improve your endurance performance and heat tolerance, but perhaps you aren’t sure how or when to do it, or even if you should. Below, I explain what you should know about heat training, which is also sometimes called heat adaptation or heat acclimation/acclimatization.

What is heat training?

Heat training is the act of intentionally exercising in a hot environment for a designated amount of time and intensity in order to stimulate physiological adaptations from a raised core body temperature. While you may get some benefits from simply spending time out in the heat or cycling or running in the heat, this doesn’t mean you are always heat training.

Exercising and living in hot temperatures provides an outside stimulus which prompts your body to make physiological changes to adapt to these strenuous conditions. Some of the ways your body adapts to the heat include increasing sweat rate to dissipate heat from your body, reducing concentration of electrolytes in sweat, increasing blood plasma volume to deliver nutrients and helping cool your body, reducing your resting body temperature, and reducing your heart rate at given exertion levels.

These physiological changes may happen just from living in hot climates but won’t have the same beneficial effects as formal heat training. To stimulate these changes, you need a certain level of exposure to the heat for certain quantities of time.

Photo by Maarten van den Heuvel on Unsplash

Get your FREE 10k trail running plan

How to accomplish heat training

Heat training protocols vary greatly, but it is generally accepted that 8 to 14 heat training sessions for 45 minutes or longer are adequate to produce physiological benefits to endurance performance and heat tolerance during exercise. Studies on heat training protocols have been tested in temperatures between 90- and 104-degrees Fahrenheit (32 to 40 degrees Celsius), and training sessions often are on consecutive days.

Short-term heat acclimation protocols of 7 days or less have also been shown to produce physiological benefits for endurance athletes, but they are less effective than longer protocols between 8 and 14 days according to an article published in 2014 in Sports Medicine.

High-intensity training sessions have been shown to be more beneficial than low-intensity training sessions for heat training, although low-intensity exercise can also be helpful according to a scientific review article published in 2015 in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sport.

Not everyone has the time, resources, or need to complete a regimented heat training protocol. If you live in a hot climate, heat training may be as easy as going out for a short ride or run when it's hotter than you are used to and doing that for consecutive days.

If you don’t live in a hot climate, then you may need to plan a trip to a hot climate country which will take time and money. You could opt for space heaters, saunas, heat chambers and other ways to simulate hot temperatures but again these are costly.

Get some FREE resources including training plans here Chili Tri

CORE Body Temperature Monitor - core temperature as a gauge

One of the best ways to find your heat training zones is to use a CORE body temperature sensor and complete a Heat Ramp Test. This test will enable you to find your current heat training zones and when you get too hot and your performance degrades. If you then go and do some structured heat training you can re-test and find out if you heat training has been effective.

You can also use the CORE to keep tabs on your body core temperature to ensure you are working optimally during training and racing. You can find out how I used the CORE monitor in my Blog.

Get your FREE 31 structured cycling sessions and training plan

Heart Rate Zones and the Heat

Heart rates are always higher when temperatures are warm and humid outside. Your heart rate increases by about 2-4 beats per minute when the temperatures rise from 60-75 degrees Fahrenheit (16 to 24 degrees Celsius) and another 10 beats per minute when temperatures rise from 75-90 degrees Fahrenheit (24 to 32 degrees Celsius).

I have tested many heart rate monitors and here are my top picks.

Additionally, when we couple high humidity with high temperatures, it becomes necessary to adjust heart rates zones for training conditions. Also bear in mind that dehydration causes an increase in heart rate. As you become dehydrated, blood volume decreases, and less blood is pumped with each stroke. A fluid loss of as little as 1% can cause your heart rate to raise 7 beats per minute.

For example, a weight loss of 1.5 pounds (0.68kg) for a 150-pound (68kg) person due to dehydration can cause a heart rate increase of 7 beats per minute. Such fluid loss is typical for an hour of outdoor moderate activity.

On these hot humid days, athletes training outdoors can expect to lose over 2 pounds (1 litre) of water per hour. It is therefore very important to pay attention to hydration as it goes hand-in-hand with heart rates and healthy exercise. You can check your specific loses by completing a sweat rate test detailed in this Blog.

As you can see using target heart rate zones in the heat is not the best way to gauge your training.

Polar H10 Heart Rate Monitor - one of the most accurate HRMs on the market £62 on Amazon

Get your FREE Running Technique Guide

Power as a Gauge

For running the best approach will be to take both power and pace into consideration. Adjusting your pace and power so that the overall effort is about the same as your session target heart rate equivalent, but also realizing that you’ll probably still end up with a higher heart rate.

Steve Palladino has a Facebook group for power-based runners. He created a calculator that will adjust for variables such as heat and elevation and you may find this is helpful.

However, you may consider retesting in the hotter weather. It’ll probably lower your Critical Power (CP) a little, but not as much as if you tried to keep your heart rate at the same level. Another possibility would be going by perceived effort and not worrying about your heart rate. Again, this will probably slow you down a little, but not as much as if you ran by heart rate.

Power is a good way to make sure you are meeting your training sessions target as a watt is a watt is a watt. If you adjust your power zones for the conditions and make power your primary cue in your runs that really count you should be in good shape.

You can also use power as a good gauge when cycling.

The photo below shows a Stryd footpod being used with a Garmin watch for running power.

Stryd footpod (get 15% off with code: coach-parnell) and Garmin Fenix 7 watch with build in running power

Get your FREE Swim Workouts for Triathletes Book

Breathing as a Gauge

If you don’t have a running or cycling power sensor, then breathing is a good indicator of intensity level as unlike heart rate is less affected by the heat.

In the heat, the heart is doing working doubly hard to move blood to the working muscle AND moving blood to the skin to dissipate heat. As a result, your heart rate will be higher but not due to running too fast. Trying to lower your heart rate to your normal heart rate zone results in running too slowly. Breathing is a better metric. As long as breathing is in the right zone, your training is in the right zone

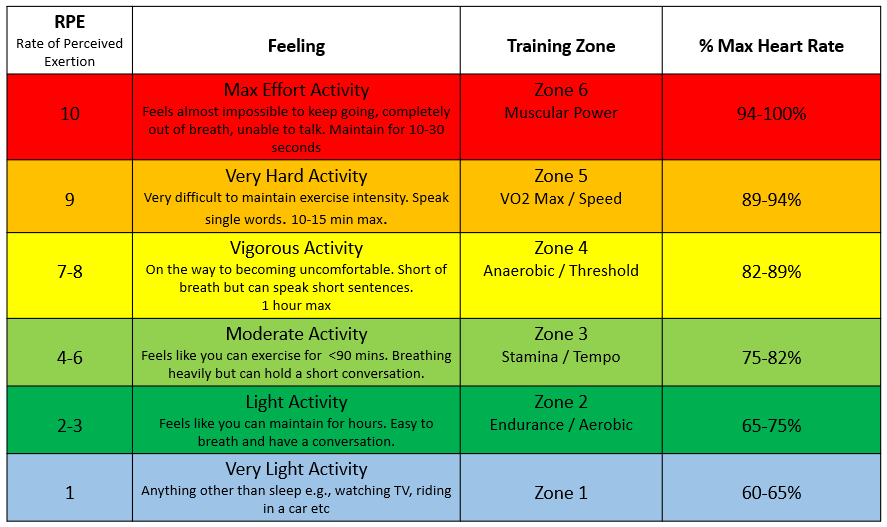

Here are the Breathing Zones or Talk Test defined by McMillan Running.:

Endurance Zone (Z1-2) – carry on a full conversation (recovery runs, easy runs, and long runs)

Stamina Zone (Aerobic Z3) – speak in 1-2 sentences (Steady State Runs, Tempo Runs and Tempo Intervals)

Speed Zone (Lactate Threshold Z4) – speak 1-2 words but definitely not a lot of talking (

Sprint Zone (Anaerobic Z5-6) – grunts and moans

Table showing Heart Rate, RPE and Talk Test

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) as a Gauge

A study in to how cold and heat affected RPE when training found that overall RPE was significantly lower in the cool than in the heat. Subjects perceived work to be harder, felt worse, and experienced greater thermal sensation in the hot condition, compared with the neutral and cool conditions.

So, like heart rate this may not be the best gauge of intensity level when training in the heat and you should consider power and breathing instead.

See the table above to see the relationship between RPE and Heart Rate Zone.

Get some FREE resources including training plans here Chili Tri

Heat Training Hack

I read this hack on Triathlon.com. Research published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine in Science & Sports shows the bathtub is a straightforward and effective tool for building heat adaptations in endurance athletes.

In the study, non-heat acclimated athletes ran a 5K time trial in temperate and hot conditions, then took part in a six-day routine involving a 40-minute treadmill run followed by either a hot-water or room-temperature soak. At the conclusion of the week, they ran the time trial again—and there was a big difference between the two soaking sets when running in the heat.

“The normal decrease in performance over a 5K time trial was 5%,” says Professor Neil Walsh of Bangor University. “This decrease was prevented in those who heat acclimated.”

In other words, the ones who soaked in the hot tub after their workouts were able to run just as fast in hot weather as they were in mild conditions. Walsh says this is because heat acclimation, even in a tub, can lower resting body temperature and switch on the heat loss mechanisms (such as sweating) earlier during exercise in the heat.

Walsh says the benefits of this protocol may last at least two weeks. To implement this practice ahead of training or racing in a warmer climate, Walsh provides the following instructions:

- Train as usual, but allot time at the end of the workout for a soak.

- Take a hot bath for 15 minutes on day one, building 5 minutes per day, until 40 minutes on day six.

- The bath should be hot, but not as hot as you can stand—Walsh recommends 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius). If in doubt, get out.

- Immersion should reach up to the neck.

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio

Get your FREE guide to strength and conditioning - includes workouts!

Hydration and Staying Safe

Make sure to drink 20 ounces (591 millilitres) to 32 ounces (946 millilitres) of fluid per hour while heat training to reduce the risk of heat exhaustion or heat stroke.

Develop a heat-training protocol with a trained professional (a qualified coach or sports physician) to maximize the gains of the protocol in context of the environment and equipment that you have available.

When training in the heat expose as much skin as possible to increase cooling through sweat evaporation and don't forget to wear sunblock.

Recognize the early warning signs of heat illness, such as heat cramps, excessive sweating, cold, clammy skin, normal or slightly elevated body temperature, paleness, dizziness, weak and rapid pulse, shallow breathing, nausea and headache.

Completing a Sweat Test is a good idea to make sure you are replacing the right amount of fluids for your training and body as every athlete is different. Here's hows to complete a sweat test at home.

Here's a recipe for a homemade energy drink.

Photo by Thao Le Hoang on Unsplash

Get some FREE athlete recipe books

When should Triathletes do heat training?

If you are planning to compete or train in a hot climate, heat training has been shown to have the most benefits for performance and comfort on endurance exercise in the heat, as compared to shorter high-speed efforts like sprinting.

Heat training has been shown to be the most beneficial for athletes completing endurance exercise, like time trials, in hot climates. These training sessions stimulate the body to reduce heart rate for a designated power output, reduce core body temperature both at rest and during exercise, improve perceptions of thermal comfort (make it feel more comfortable in hot temperatures), and increase time to exhaustion during time trials.

One study shows that short-term heat training (five 60-minute sessions) improves aerobic performance, while other research demonstrates that heat training improves cycling time trial performance in the heat by as much as 16 percent (though it didn’t improve VO2 max or peak aerobic power output).

While there is more clear evidence to support using heat training to improve performance when actually training in the heat, results are mixed as to whether heat training benefits performance while riding or running in cool temperatures.

Studies show that if you are completing heat training to perform in a hot event, the closer to the event date the better. For every day that you are not exercising or living in the heat, there is about a 2.5 percent loss in heart rate and core temperature cooling gains.

Your heat acclimation protocol should generally start two to three weeks out from your race. You will want to stop your heat acclimation seven days before your race to mitigate any negative impact of the heat on-site. The effects of heat acclimation training can last for upward of 10 days.

There is no single “optimal” Heat Acclimatization (HA) induction protocol that applies to all athletes. Ten days of consecutive exercise-heat exposure for 90 minutes in 30°C wet-bulb globe temperature is a good starting point for customization. HA should reflect the expected competition environment and be sport-specific whenever possible. Incorporating several induction methodologies may allow high training quality while acclimating to the heat.

While the ideal timing of HA prior to competition is debated, current evidence indicates HA should be completed 1–3 weeks prior to competition to allow sufficient recovery from heavy training loads (including HA) and enable a training taper.

Intermittent exercise-heat exposure, heat re-acclimation, sauna bathing, or hot water immersion can be used to sustain or rapidly regain HA throughout the season. Despite substantial progress over the last several decades, gaps in knowledge remain requiring future work regarding exercise and heat including the female response/adaptation, the immune and microbiome response/adaptation, and the genetic and epigenetic connection with HA induction and decay. Prior et al, 2018.

While athletes of all abilities benefit from heat training, the physiological benefits may stay longer for more highly trained athletes compared to athletes who are less trained, based on their VO2 max.

If you are not able to complete heat training right before your hot event, then don’t worry as scientists have come up with ways to top up the benefits previously gained. A study published in 2021 in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise showed that five days of heat training were enough to regain the sweat adaptation benefits of a 10-day heat training routine performed more than 30 days prior. If you have a specific event, you are using heat training for, ideally you are completing the heat training as close to event day as possible. If this isn’t possible, a refresher of five days of heat training could be helpful.

Even for non-professional triathletes, if you are planning to ride or run in hot temperatures, heat training prior to those rides or runs can reduce your suffering, increase your overall endurance performance, and reduce your risk of heat stroke and other heat-related medical issues. These benefits will exist no matter what level of rider you are.

.jpg)

Photo by Coen van de Broek on Unsplash

Get some FREE resources including training plans here Chili Tri

When does heat training show little benefit?

While studies have shown heat training to be beneficial for endurance performance, the same cannot be said for short duration efforts, such as sprinting.

A systematic review published in 2014 included eight studies investigating the effectiveness of short-term heat acclimation training on physical performance. (Limitations for this review include the studies having a cumulative moderate level of bias, only two of the eight studies were randomized controlled trials, and only one of the studies focused on women participants.) The researchers concluded that 7 or less heat exposure sessions may benefit aerobic-based tests but not anaerobic power efforts.

Not only has heat training not shown to benefit athletes performing short efforts, but the stress put on the body while exercising in the heat may be detrimental to training for sprint events.

Heat training has been shown to be most effective for endurance exercise in the heat. Its caveats include that it may or may not help with endurance efforts in cool temperatures, and it probably doesn’t benefit anaerobic type efforts in either hot or cool temperatures.

Conclusion: Heat Training

Triathletes of all levels can benefit from heat training, especially if they are planning to train or compete for 20 minutes or more in the heat. This heat training depends on if they have the time and resources to complete 8 to 14 days of consecutive heat training sessions close to their event, and/or the addition of a five-day heat training top-up closer to their event. Many protocols exist for heat training, and athletes should assess their goals, time, resources, and interest in preparation to decide if heat training is worth it for them and how to integrate it into their performance plans, without risking safety.

The best ways to gauge intensity level are power and breathing (talk test) to ensure you are training in the right zones. You can also use a CORE body temperature monitor to work out your optimal heat range and gauge if heat training is working for you using a Heat Ramp Test.

It's important to stay safe and not over extend yourself when training in the heat. Completing a sweat test to understand your specific hydration needs is recommended. I would also recommend taking regular blood pressure measurements to make sure you are not putting your body under too much stress.

Get some FREE resources including training plans here Chili Tri

Karen Parnell is a Level 3 British Triathlon and IRONMAN Certified Coach, 8020 Endurance Certified Coach, WOWSA Level 3 open water swimming coach and NASM Personal Trainer and Sports Technology Writer.

Karen has a post graduate MSc in Sports Performance Coaching from the University of Stirling.

Need a training plan? I have plans on TrainingPeaks and FinalSurge:

I also coach a very small number of athletes one to one for all triathlon and multi-sport distances, open water swimming events and running races, email me for details and availability. Karen.parnell@chilitri.com

Get your FREE Guide to Running Speed and Technique

Get your FREE Swim Workouts for Triathletes E-book

Get your FREE Open Water Swimming Sessions E-Book

.png)

FAQ: Triathlon Training in the Heat

Is 90 degrees Fahrenheit / 32 degrees Celsius too hot to run?

Generally, when the heat index is over 90 degrees Fahrenheit, you should use extreme caution when heading outdoors for activity or intense exercise. When the temperatures are high, there is an increased risk of serious heat-related illnesses.

Does working out in the heat help lose weight?

Sweating is the body's natural way of regulating body temperature. It does this by releasing water and salt, which evaporates to help cool you. Sweating itself doesn't burn a measurable amount of calories, but sweating out enough liquid will cause you to lose water weight. It's only a temporary loss, though.

Why is it harder to run in the heat?

The heat is the most difficult element for runners to compete in and race well. With the rise in core body temperature, a runner will have less oxygen available to working muscles, become dehydrated, and suffer a decline in performance.

What alternatives do we have to exercising in the worst heat of the day?

If you experience a few days of extremely hot temperature where you live then consider getting up really early to complete your training before it gets too hot, head to an air conditioned gym and concentrate on strength and conditioning or use a treadmill or indoor bike or prioritise your swimming sessions.

Is training in the heat beneficial for triathletes?

Training in the heat can provide several benefits for triathletes:

- Heat acclimation: Exposing your body to hot conditions during training can improve heat acclimation and enhance your ability to perform in hot race conditions.

- Increased sweat rate: Training in the heat stimulates increased sweating, which can improve thermoregulation and help your body become more efficient at cooling itself.

- Improved cardiovascular function: Training in the heat can increase plasma volume, lower heart rate, and improve cardiovascular efficiency, leading to better endurance performance.

- Mental toughness: Enduring challenging training conditions can strengthen mental resilience, helping you push through discomfort during races.

How can I gauge my training zones in the heat?

Training zones may need to be adjusted when training in the heat due to increased heart rate and perceived effort. Here are two methods to gauge your training zones:

- Perceived exertion: Use the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale to assess your effort level. Adjust your target RPE based on the heat and humidity, understanding that the same effort may feel harder in hot conditions.

- Heart rate monitoring: If you use heart rate zones for training, be aware that your heart rate may be elevated in the heat. You may need to adjust your heart rate zones accordingly. Consult with a coach or sports scientist to help you recalibrate your zones.

What precautions should I take when training in the heat?

When training in hot conditions, it's important to prioritize safety and minimize the risk of heat-related illnesses. Here are some precautions to take:

- Hydration: Stay hydrated by drinking fluids before, during, and after your training sessions. Aim to replace fluids lost through sweating.

- Electrolyte balance: Replenish electrolytes lost through sweating by consuming electrolyte-rich beverages or supplements.

- Timing of training: Consider training during cooler parts of the day, such as early morning or evening, to minimize heat exposure.

- Proper clothing: Wear lightweight, moisture-wicking clothing that allows for better heat dissipation and evaporation of sweat.

- Sun protection: Protect yourself from the sun by wearing a hat, applying sunscreen, and wearing sunglasses.

- Gradual adaptation: Gradually increase the duration and intensity of your training in the heat to allow your body to adapt gradually.

Are there any potential risks of training in the heat?

Yes, training in the heat poses certain risks, including:

- Dehydration: Inadequate fluid intake can lead to dehydration, which can impair performance and increase the risk of heat-related illnesses.

- Heat exhaustion: Prolonged exposure to heat can result in heat exhaustion, characterized by symptoms like dizziness, nausea, weakness, and excessive sweating.

- Heatstroke: Heatstroke is a severe condition that requires immediate medical attention. It can occur when the body's core temperature rises dangerously high.

Should I modify my training plan when training in the heat?

Yes, it may be necessary to modify your training plan when training in the heat. Here are some considerations:

- Adjust intensity: Lower the intensity of your workouts, especially during intense heatwaves, to prevent overheating and reduce the risk of heat-related issues.

- Increase recovery time: Allow for longer recovery periods between workouts to give your body time to adapt and replenish energy stores.

- Modify workout timing: Consider shifting high-intensity workouts or long endurance sessions to cooler parts of the day.

Always listen to your body, pay attention to signs of heat-related stress, and adjust your training accordingly. It's important to prioritize safety and well-being during training in hot conditions.

References

Bicycling.com

https://www.bicycling.com/training/a40156038/benefits-of-heat-training-for-cyclists/

Gearedup.biz

80/20 Running

https://www.8020endurance.com/topic/heat-humidity-and-hr/

McMillan Running

https://www.mcmillanrunning.com/the-talk-test-the-worlds-easiest-training-tool/

Maw GJ, Boutcher SH, Taylor NA. Ratings of perceived exertion and affect in hot and cool environments. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1993;67(2):174-9. doi: 10.1007/BF00376663. PMID: 8223525.

Adaptation to Hot Environmental Conditions: An Exploration of the Performance Basis, Procedures and Future Directions to Optimise Opportunities for Elite Athletes

Adaptations and mechanisms of human heat acclimation: Applications for competitive athletes and sports

Short-Term Heat Acclimation Training Improves Physical Performance: A Systematic Review, and Exploration of Physiological Adaptations and Application for Team Sports

https://www.triathlete.com/training/this-heat-adaptation-hack-will-surprise-you/

#traithlontrainingplans #runningtrainingplans #swimmingtrainingplans #triathlon #cycling #running #trainingintheheat #heattraining